I’m an author and designer in Dublin, Ireland, where I specialise in making paper props for period filmmaking—old newspapers and stuff. I designed the map in the latest Indiana Jones movie, I’ve made tons of pieces for Steven Spielberg and Wes Anderson, and please don’t overlook my contributions to Chicken Run II: Dawn of the Nugget!

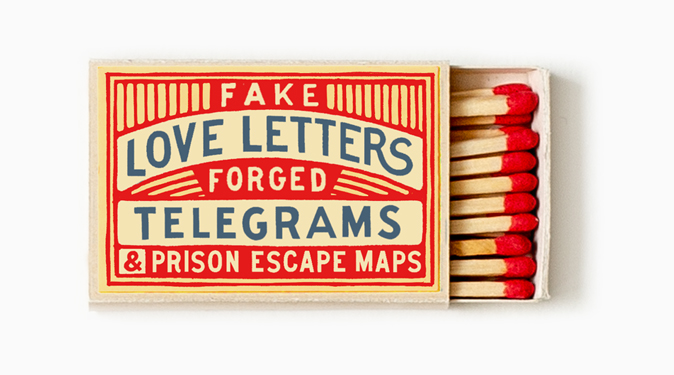

My first book, Fake Love Letters, prompted Jeff Goldblum to write that “Annie makes the unreal seem hyperreal, and the real more supremely alive and utterly magical”. My second book, Letters from the North Pole, was picked by the Sunday Times as one of their top 21 children’s books of the year. I’m now working on my third book, here in my studio in Dublin.

I also send out the occasional newsletter, which you might like to sign up for—have a look and see if it’s your cup of tea.

DESIGNING GRAPHIC PROPS FOR FILMMaking

{Occasionally Asked Questions}

How did you start working in graphic design for film?

My first job after I graduated was on the third series of The Tudors and no job since then has been as exhilarating as that first season I spent on a set, surrounded by beautiful princesses in corsets drinking coffee out of styrofoam cups. At first, it didn’t make sense to me that they’d be looking for a full-time graphic designer on a series that was set in a time before graphic designers existed. But just because there were no graphic designers in the court of Henry VIII didn’t mean there wasn’t any graphic design: it was just that, at that time, craftsmen produced the graphics. So, if the king wanted to chop his wife’s head off, for example, he would need a death warrant, and if he needed a death warrant, he would need a calligrapher. Today, in filmmaking, it’s the graphic designer’s job to imitate what that calligrapher might have created—or, at least, to hire a real calligrapher to help us out.

Is the role as exciting as it seems?

Yes! Anyone who works in film and tells you it’s not exciting is just pretending to be jaded, don’t worry. We’re all here for the thrill of it: nobody is here for the health benefits. You do get a little more used to it as time goes by, but seeing your work on a cinema screen, even fleetingly, even in the blurry background, never stops being exciting.

How much of your work is seen by the cinema audience?

I would say hardly any of it. Maybe 90% of what we make for a film belongs firmly in the background. If the audience is focussing on the props then “we’re doing our job wrong”, as my pal the prop master Robin Miller always says. It’s just that these things need to be finely detailed in order to disappear. And sometimes what we create isn’t actually for the cinema audience at all. Film sets don’t look like the beautifully composed pictures we see on the cinema screen: the reality is that they’re full of cables, floodlights, and crew members standing around in North Face jackets—so, dressing this weirdly artificial environment with some small authentic details can help create a more fully realised world for the actors to work in.

What is your favourite period to work to?

I love all period filmmaking and prefer it to anything contemporary—and I definitely don’t like science fiction (it took me a long time and one failed attempt at futurism to realise that). What can I say—I just really like antique documents and old shopfront signage. My speciality is in creating lettering that looks like it was painted up by a layperson rather than a professional designer. It’s tricky designing something that doesn’t look like it was made by an art department when you’re in the art department: you really have to shake off your digital instincts and step in to the shoes of the character—or the time or place—that you’re designing for. I love that challenge. If something was made by hand at the time, then I try to make it by hand now.

Should I move to Hollywood?

Oh no, I’ve never set foot in Hollywood. We made Penny Dreadful in a little seaside town in County Wicklow, so you never know what’s going on right around the corner. I think you have a better chance of employment starting local than you do hopping off a bus on Sunset Boulevard with your CV and your backpack, which is how I’m imagining you now, wistfully. Part of me is wishing you a wonderful adventure and the other part of me is thinking look, come on, you should really be at home categorising your serifs, no?

But I only want to work on big box-office movies…

Er, you might want to reconsider why you want to be a graphic designer for film. Is it down to your love of old-fashioned prop-making using a variety of tangible and traditional graphic materials, or is it because you want to stalk Bill Murray? The thing is, it doesn’t really matter if you’re on a small TV show or a cinema blockbuster, learning how to make this stuff is what’s important. My most fun job was on a show called Camelot which you will have no recollection of whatsoever, but I got to make some rather convincing ancient tombstones by carving Roman lettering in to soft, wet clay.

What was it like working with Wes Anderson?

Wes Anderson is the most experimental and hands-on director I’ve ever worked with, and I worked closely with him and his production designer, Adam Stockhausen every day. The Grand Budapest Hotel was my move from TV to film, and it was an incredible rollercoaster from the moment I got the first call from the producers, to the winter I spent with the cast and crew in the fictional Empire of Zubrowka, to the day I sat down in the cinema to watch the movie for the first time. I doubt I’ll work on a more beloved film that pays so much attention to graphic design again in my lifetime, so not a day goes by when I don’t thank my lucky stars (and Wes and Adam!) for that opportunity.

Where can I read more?

My book, Fake Love Letters, Forged Telegrams, and Prison Escape Maps: Designing Graphic Props for Filmmaking. Published by Phaidon, it’s a look at the process behind designing graphic props, with some of my favourite personal stories from working on the sets of films like Grand Budapest.

If you’re looking for interviews about film design then this conversation with Roman Mars on his 99% Invisible podcast is a good place to start. My interview page has some other interesting links, too, or you can sign up for my newsletter.

My Domestika course is an in-depth tour in creating graphic props for film and is available to buy online now. I also run in-person workshops here in Dublin, you can read about them here.

(I’m really sorry that I can’t give any student interviews at the moment, but the links above should answer all of your questions and you are welcome to quote anything you see fit in your essays. Good luck!)

Tracy in Isle of Dogs, in front of eighteen maps of the Japanese archipelago, each one individually hand-drawn.

I’m starting my first film job tomorrow, any tips?

Huzzah! Wear old clothes, be in bed by 10pm every night, and never, ever use glue on a cutting mat.